Turbulent the sea -

Across to Sado stretches

The Milky Way.

- Basho

The Arakis come from the village of Shinmachi, or 'new town,' on Mano Bay, which lies on the western shore of Sado, the largest Japanese island in the Sea of Japan. The island covers about 330 square miles, comprising two parallel mountain ranges with a central plain between them, and lies about 14 miles off the coast of Niigata. It was long regarded as a remote and forbidding place.

A 17th century map of Sado Island.

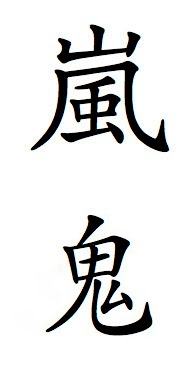

The first reference to the island appears in the Nihon Shoki, an 8th century chronicle of Japan's earliest history, which recounts (according to W.G. Ashton's 1896 translation) that in 544 AD "at Cape Minabe, on the northern side of the Island of Sado, there arrived men of Su-shēn in a boat, and staid [sic] there. During the spring and summer they caught fish, which they used for food. The men of that island said they were not human beings. They also called them devils, and did not dare go near them.”The ‘men of Su-shēn‘ are surmised in a footnote to have been from northeastern China, ancestors of the Manchus. It is interesting, though likely a coincidence, that an earlier known written form of the Araki name on Sado was 'storm devil.'

Araki, written as "storm devil."

The Araki family may have descended from 大の荒木の値, or O no Araki no Atai, who was sent by the Emperor Seimu to Sado as a governor either in the second century AD or the fourth century AD (depending on the scholar or the source). Seimu is known for having vastly expanded the number of provinces under imperial control, dispatching officials as imperial representatives to the far reaches of his realm. There is a shrine to this Araki in Izumi. While this Araki (荒木) uses different characters (meaning 'rough tree' or 'fresh tree'), Masako recalls her mother saying the Araki family originated in Izumi.Today, the Araki name is written as the still imposing but less threatening 'storm castle.'

Araki, written as "storm castle."

The island's remoteness made it a favored place of exile.Emperor Juntoku, the third son of Emperor Go-Toba, was banished to Sado in 1221 after his participation in his father's unsuccessful attempt to displace the Kamakura shogunate and reassert Imperial power.

Legend has it that as Emperor Juntoku stepped ashore at Mano Bay, not far from where the Araki brewery later stood, the waves formed the shape of chrysanthemum petals, comforting the emperor. The chrysanthemum is the crest of the royal family in Japan. Kikunami, or Chrysanthemum Wave, was the last label under which the Araki family bottled sake. It recalls the emperor's exile.

Araki brewery's Kikunami label.

Nichiren, the Buddhist monk and founder of Nichiren Buddhism, was exiled to Sado for three years beginning in 1271.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi's 1831 woodblock print of Nichiren going into exile on Sado island.

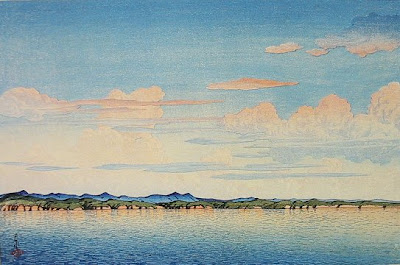

After a brutal winter on the east side of the island, Nichiren moved to the gentler shores of Mano Bay.

Hasui Kawase's 1921 woodblock print of Sado's Mano Bay.

The late 16th century discovery of large deposits of gold-bearing quartz on the island led to an influx of convicts to work the mines that financed the Tokugawa shogunate. The island's population rose to its highest during the operation of the mines in this era (The mines did not shut down completely until 1989).

Sado became a bastion of Christianity around that time. According to a history written by the German professor J.J. Rein in 1884, thousands of Japanese Christians

were banished to the mines of the island of Sado. Their personal goodness and their fidelity to their faith led the governor of the island, called Okubo Nagayasu. to the adoption of Christianity. Griffis mentions that he shortly afterwards became the head of a Christian conspiracy, which had as its object to make the island of Sado independent and to make Okubo its ruler. The signatures of the conspirators, sealed with their blood, were found attached to a document, together with other certain evidences of the design. Whether this story was well founded, or whether the whole affair was not a malicious invention of the enemies of Christianity, and in particular of the apostates, who were then busily laying informations everywhere, I could not ascertain.Rein's reference is to William Elliot Griffis' History of Japan from 660 B.C. to 1872 A.D, which states that

In 1610, the Spanish friars again aroused the wrath of the Government by defying its commands and exhorting the native converts to do likewise. In 1611, Tokugawa Ieyasu obtained documentary proof of what he had long suspected, viz., the existence of a plot on the part of the native converts and the foreign emissaries to reduce Japan to the position of a subject state. The chief conspirator, Okubo, then Governor of Sado, to which place thousands of Christian exiles had been sent to work the mines, was to be made hereditary ruler by the foreigners. The names of the chief native and foreign conspirators were written down, with the usual seal of blood from the end fo the middle finger of the ringleader. With this paper was found concealed, in an iron box in an old well, a vast hoard of gold and silver.The poet Matsuo Basho wrote about the island in his 17th century travelogue, Narrow Road (translated by Hiroaki Satō in 1996):

From the place called Izumozaki in the province of Echigo, Sado Island, it is said, is eighteen li away on the sea. With the cragginess of its valleys and peaks clearly visible, it lies on its side in the sea, thirty-odd li from east to west. Light mists of early fall not rising yet, and the waves not high, I feel as though I could touch it with my hands as I look at it. On the island great quantities of gold well up and in that regard it is a most auspicious island. But from past to present a place of exile for felons and traitors, it has become a distressing name. The thought terrifies me. As the evening moon sets, the surface of the sea becomes quite dark. The shapes of the mountains are still visible through the clouds, and the sound of waves is saddening as I listen.

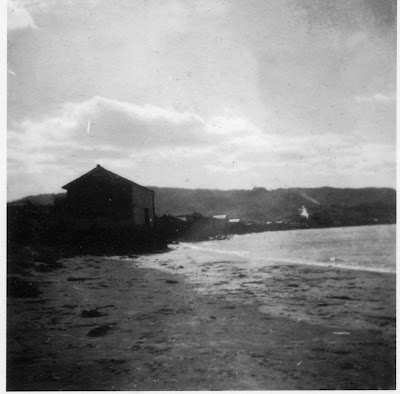

Beach at Mano Bay with the Araki compound in the background.

The Arakis were the most prominent family in Mano-Shinmachi and were among the largest landowners on the island. Under the feudal system that remained in effect until after World War II, peasants living on the Araki land were obliged to pay a rice tax to the family. Much of that rice was used to brew sake. Masako recalls the peasants coming to negotiate the rice tax each year around harvest time when she was a girl.The large building pictured above was used to store boats and other equipment in the compound where the sake brewery stood. Masako and her schoolmates would swim daily at this beach in the warm-weather months. At the near end of the buildng above, she recalls, there were stone steps into the water where the men would catch large horsehair crabs (Erimacrus isenbeckii, (Japanese: ケガニ kegani). The family lived in a house in the compound on the opposite corner in this picture, facing the street. The compound had a well with reputedly the best water in Mano-shinmachi, which the family drank and used for brewing sake. The family maintained a large house for entertaining guests further south on the other side of the street. The main part of that guest house burned down in 1953. The remaining portion is still owned by the family today.

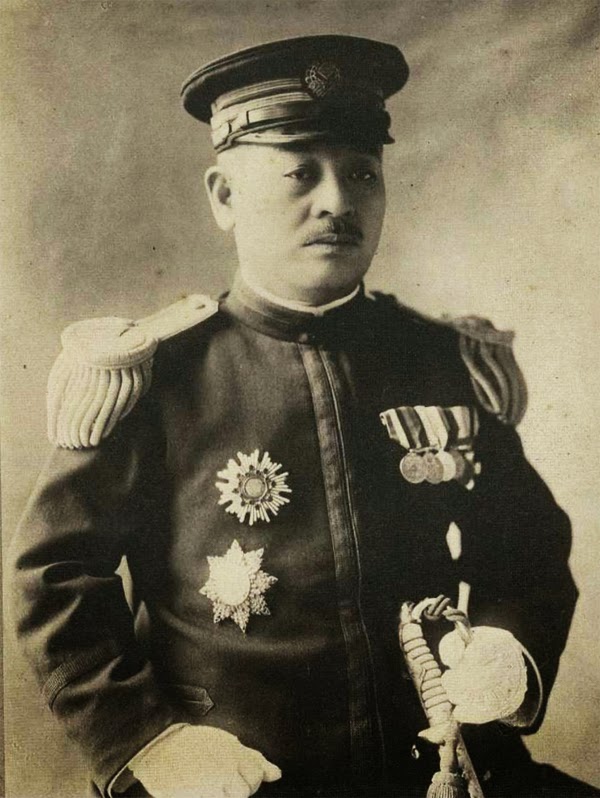

Araki Keisai (嵐城松蔵)

Masako's grandfather,

from the neighboring village of Hatano.

Only girls were born to the two generations of Arakis preceding Masako and in order to keep the land in the family, the men who married the female heirs of those two generations took the Araki name. The first was Nakagawa Mastuzo, known by his art-name or go (号), Keisai, who married Masako's grandmother, who was an only child.Masako's grandfather,

from the neighboring village of Hatano.

Keisai and Masako's grandmother (name unknown) had four daughters, who were named - from eldest to youngest - Masu, Gen, Teru and Chizu.

The Araki family under Keisai.

Pictured above in the back row are Gen, the favored daughter, and Keisai, who took Araki name. In the front row, from left to right, are Masu, Chizu, the stepmother of Masako's grandmother, Teru and Masako's grandmother, holding a baby boy. The boy was Masu's son from her first marriage, which ended because of Keisai's displeasure with the husband. According to family lore, the man went on to become mayor of Tokyo. The boy died in infancy.Despite being born to privilege, Keisai's four daughters had troubled lives. Masu married again and bore children, but died young of tuberculosis. Gen, the second eldest, married a man of means and bore a daughter, but divorced and moved to live alone with her child in Tokyo, supported by an Araki stipend. Teru loved a cousin whom she was forbidden to marry and so became a schoolteacher in Tokyo until she was recalled home to marry Masu's widower at Keisai's behest. Chizu, the youngest, aspired to be an opera singer. She married, bore a son, but died young of tuberculosis, as did her husband, leaving their son orphaned. The son, Ishizuke Eiichi, later went to live in Teru's household.

Gen, playing Koto on the far right, at her college dormitory with friends. A cousin is reading a book.

Teru, at about age 25.

This is a copy of a picture Teru gave her cousin, Nakagawa Seigo, with whom she was in love but was forbidden to marry because the bloodlines were too close.

Nakagawa Seigo

This is a picture that Nakagawa Seigo gave Teru at around the same time.

The back of picture above.

The date is April, 7th year of the Taisho era, or 1918. The large character is the second character in the name Seigo. Go means 'me.' It is, apparently, his signature.

Nakagawa Seigo, wearing his cap from the famous Daiichi Koto Gakko.

Seigo attended Daiichi Koto Gakko, or First Higher School, the most prestigious high school in Japan at the time. Its grounds now form the heart of Tokyo University's Komaba campus. Seigo went on to graduate from Tokyo University and become an executive with the shipping company, Nihon Yusen Kaisha, or NYK Lines.

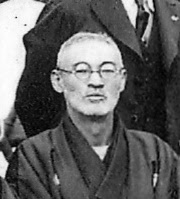

Nakagawa Kenzo

Seigo was the son of Nakagawa Kenzo, a graduate of Japan's Tokyo

Imperial University Law School who served as governor-general of Taiwan

from 1932 to 1936. Masako's father, Jisaku, visited him there in 1935 or 1936 and returned

to Sado with crates of fresh fruit, including pineapples. It was the first time

that Masako had tasted pineapple (she remembers that it didn't taste very good).

Nakagawa Kenzo later served as chairman of Zen Nippon Koku, the precursor to Japan Airlines. Masako met him when she was a child and she and her mother visited the Nakagawa home at Seijo Gakuenmae in Tokyo. She remembers the home was a Sukiya-zukuri style house built of beautiful wood with a view of Mount Fuji.

Masako would later visit the home when she was in college and the Nakagawas would feed her, because food was scarce in Tokyo. She remembers that they had bread made with yeast from New York, where Seigo and his wife had lived before the war.

Another son of Nakagawa Kenzo, Nakagawa Toru, later served as Japan's ambassador to the United Nations in New York where Masako met him at a reception at the ambassador's residence on 72nd Street in 1974. Nakagawa Toru studied at Oxford and later he was charged with attending to the Crown Prince when the prince was at Oxford. While Nakagawa Toru had been ambassador to Britain and the Soviet Union, his first secretary was the father of a young woman who later studied at Harvard. Nakagawa Toru was likely the liaison between the young woman, Masako, and the Crown Prince. The prince and Masako dated and later married and are now Emperor and Empress of Japan.

Nigami Jisaku

Masu, Keisai's eldest daughter who had divorced her first husband at Keisai's behest, married Nigami Jisaku.Jisaku and Masu had four children, including three boys, Ken, Junjiro and Katsusaburo, and one girl, Yoshiko. When Masu died of tuberculosis, Jisaku married her sister, Teru. Jisaku and Teru had three more children: Masako, Keishiro and Goro.

The boys' names, except for that of the oldest, Ken, reflect the order in which they were born: Junjiro(淳二郎), Katsusaburo(勝三郎), Keishiro (敬四郎)and Goro(悟郎). Goro is pronounced the same as 五郎, which means means the fifth. ”郎” is a very popular ending for male names just like "子" is for females.

Katsusaburo did not like his name and changed to Kahei, a sort of family art-name, or Yagō (屋号), by which the family had long been known in Mano-Shinmachi.

Nigami Jisaku in a photo taken for his college application.

Jisaku came from Niibo, two villages away on Sado, and went to study at Tokyo Technical University (Tokyo Kogyo Daigaku) where he graduated with a degree in applied chemistry.

Another picture of Jisaku taken for his college application to Tokyo Kyogo Daigaku.

Keisai's funeral.

When Keisai died, Teru was pregnant with Masako. Jisaku appears at Keisai's funeral alone with his four children.

Jisaku at Keisai's funeral with Ken (in a cap to the left of Jisaku), Junjiro (beside Jisaku in cap) and Yoshiko and Katsusaburo in foreground.

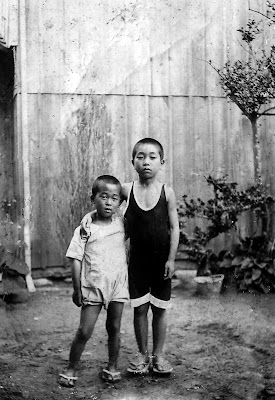

Junjiro and Ken.

This picture was taken around the time of their mother's, Masu's, death from tuberculosis. Both boys died at the age of 23, also from tuberculosis.

Nigami family wedding.

This is the wedding of Nigami Teiichiro, Jisaku's nephew, shortly after Jisaku married Teru. In the back row, from left to right, are a niece of Jisaku, Nigami Yosaku - Jisaku's brother and head of the Nigami household as well as father of the groom, two of Jisaku's sisters, another of Jisaku's nephews, Teru and Jisaku. In the front row, left to right, are Yoshiko - Jisaku's daughter by Masu, Nigami Yosaku's wife and mother of the groom, Teiichiro - the groom, Shizue - the bride, Jisaku's mother and an unknown boy.Jisaku's mother died when Masako was in the third grade in the spring following the summer that Jisaku died. Jisaku's mother wasn't told of her son's death.

1935 ceremony in honor of Keisai to commemorate his founding of the Sado Agricultural Union.

The Araki family is at the center-right in this photo.

Detail from Keisai memorial photo.

In the back row are Ken, Junjiro, Eiichi and Tsuji (the family's head housekeeper) holding Keishiro. In front, from left to right, are Jisaku, Teru holding Goro, Masako, Yoshiko and Katsusaburo.

Tasuku's father, Miyamoto Haruji.

Sitting to the left of the Shinto priest is the father of Miyamoto Tasuku. Masako was expected to grow up and marry Tasuku. Because Tasuku's older sister had attended the prestigious Japan Women's University (日本女子大学 Nihon joshi daigaku), Masako's mother arranged for Masako to attend as well, to help Masako integrate into Tasuku's family. The marriage never took place because Tasuku claimed that he suffered heart problems and believed his health would cast a pall over any marriage. In fact, he lived as a bachelor until his death in his eighties.Jisaku died in 1937 while on a business trip to Hokkaido. He was heading toward Japan's Karafuto Prefecture, as Southern Sakhalin Island was then known. En route, he stopped in Iwanai, a town on Hokkaido's west coast where many former Sado residents had moved. Jisaku collapsed at the train station and was administered to by the staionmaster in the minutes before he died, presumably of a heart attack. As it was the height of summer and there was no refrigeration to keep the body, Jisaku was cremated at Iwanai and his ashes sent back to Sado.

Funeral procession for Araki (Nigami) Jisaku down Mano-Shinmachi's main street. The banner in the foreground reads "condolences for the deceased Araki Jisaku."

Araki (Nigami) Jisaku's funeral.

Detail from Jisaku's funeral photo.

Masako, on the left, is wearing a dark kimono with a light obi next to Yoshiko, who is wearing glasses. The man holding something beside Yoshiko is Eiichi, who grew up in the household after his parents died when he was three. Junjiro is the young man wearing a dark robe and white mantle, identifying him as the chief mourner. Katsusaburo is at the right, holding flowers. Ken, the family's first born, had already died of tuberculosis. Teru, their mother, is standing between Junjiro and Katsusaburo. The child in front them is Keishiro.After Jisaku's death, Teru took over running of the household and the Araki business interests.

Years after Jisaku's death, when Masako was in late elementary school, she was with her brothers Kahei and Junjiro when they found a letter in the kura, or storage building, written by Jisaku to a man named Yamamoto, a Sado native who would later become Japan's Minister of Agriculture. Yamamoto was acting as a go-between for the Arakis to find a suitable man to marry Masu and had approached Jisaku. In the letter, Jisaku declined the proposal, saying that he had plans to build a chemical plant in China with a classmate, the son of a wealthy Chinese family. Kahei read the letter aloud and the children, shocked, all laughed. Had Jisaku not been persuaded, none of them would have been there.

It is not clear what changed Jisaku's mind. Masako remembers that Jisaku had a large map of Japan in the house, marked with oil derrick symbols and wonders if Keisai didn't offer to support Jisaku's entrepreneurial ambitions.

Wayo Joshi Daigaku reunion at Lake Kamo, Sado.

Mako's mother at the end of the row on the left, looking across, with classmates and faculty from Wayo Joshi Daigaku, or Wayo Women's University, the college she attended in Ichikawa, just outside of Tokyo. The man wearing the hat is the university president. Friends from the school came to Sado during the summers to visit.

Araki brewery worker goes to war.

This photo commemorates the departure of a brewery worker to the war. In the back row, from left to right, are Araki brewery workers. The tallest is the son of the chief brewer. In the front row, from left to right, are Jinjiro (with glasses and probably already dying of tuberculosis), a brewery worker (with hat and flag) leaving for the war, Goro (the small boy) and Keishiro, and another brewery worker. The young worker who went to war died defending Iwo Jima.After the war, the Arakis lost most of their land in the 'emancipation of farmland' reform under General MacArthur. They were left with timberland on one of Sado's mountains, from which they shared periodic revenue with the provincial government. They were also left with the brewery and continued to make sake until the 1990s.

Araki family, circa 1950.

This photo was taken in a portion of the guest house in Mano-Shinmachi that later burned down. By this time, the family had moved from the brewery house to this house. In the front row is Teru holding Kaichiro (Kahei and Yasuko's son), Kahei, Goro and Kahei's wife, Yasuko, holding her daughter Minako. Standing in the back are Masako and Keishiro. Keishiro, a talented drummer, killed himself at the age of 22. He died of an overdose of sleeping pills and was found by Goro who lived near him in Tokyo.